Why I Write About Suicide

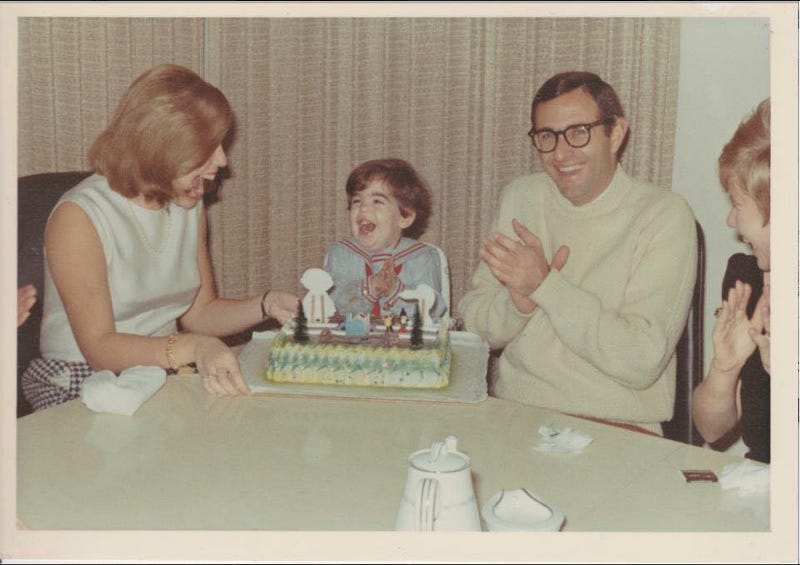

You may be thinking to yourself — if you’re thinking anything besides “I wonder where he got that Snoopy cake in the picture? And how many…

You may be thinking to yourself — if you’re thinking anything besides “I wonder where he got that Snoopy cake in the picture? And how many Weight Watchers’ points do you think it is?” — “This guy is a sitcom gag writer. Where does this shmegegge get off penning a serious piece about mental health?’

Now mind you, this could be a trick question. No one ever became a comedian because their relationship with their mother is TOO GOOD. Or they were TOO POPULAR on the schoolyard playground.

It’s true, I have been on 22 different sitcoms in 22 seasons including every failed program of the 90's, 00's and 10's. And it’s an immutable fact that I’m responsible for more dead pilots than Malaysia Airlines. So yes, I am probably better suited for writing Kimmy Gibbler bits than an advice piece about surviving the deleterious impact of familial suicide.

And yet, suicide is the topic I most frequently write about. Well suicide and politics. And 80s indie rock, fatherhood, the Brady Bunch, the history of the San Fernando Valley, depression, aging, hot dogs, The Dodgers, pastrami and getting trapped in my own wet suit. Okay fine. But suicide is ONE of my recurrent fascinations.

That’s because, just about ten years ago, my Dad took his own life. Completely out of the blue. In fact, with his tan skin, full head of hair, Fila jackets and ability to let problems roll off his back, I’ve often said he was the person in my entire life I’d least expect this from. And he was the person in my life up to that point, who I was most likely to negatively measure my own sense of well-being against.

Even with nearly a decade of pondering and processing behind me, it still feels like a morbidly unlikely dream that I just need to snap out of. And then go tell my dad about this awful nightmare.

Like I said, my dad left us about ten years ago. For the next eight years, I grieved quietly, privately and discreetly. Of course those closest to me knew about my loss. But most people once removed from my innermost circle would have no idea. Just that I liked to binge eat, ugly cry and that I loved me my Lexapro.

It felt like I was keeping a giant secret. And it didn’t feel right. Like I was withholding an essential (or the most essential) piece of my personal narrative. At an age when I was hankering to express myself more fully and transparently. Not to mention using the word “hankering” more often.

So for the last two years, I literally can’t shut up about suicide — the taboo topic which I silently held inside for the previous eight. I’ve written 4 Huffington Post pieces on suicide, ranging from the immediate emotional trauma to a more clear-eyed search for answers and meaning. I’ve touched on it during stand up sets and numerous podcast interviews. I even wrote a tragi-comic TV pilot about the destruction suicide wrought on an Encino Jewish family eerily akin to my own.

This piece won’t be about rehashing the specifics of my family’s loss. You can find those on my HuffPost page or you can ask my agents to send you a tragi-comic half hour pilot. Instead I’m interested in exploring why, as a writer, I feel the need (or even compulsion) to keep returning to a subject matter that I know will engender pain. And binge eating, ugly crying and even more Lexapro.

Why do I keep sticking my hand in the flame of a Chanukah candle? Why take a dinghy back to the beaches of Dunkirk? It’s not like I have some gin-soaked copy editor demanding I make deadline at Glock point.

But I’ll answer the first question with a follow up question: If you keep coming back to a topic, especially one as hurtful and traumatic as a dad’s suicide, is it really by choice? To keep revisiting the pain, to continually provoke the tears and PTSD shivers, there must be a need. A reason. A wound not fully healed.

I never thought the suicide survivor’s would be a club that I’d ever be part of. Well that’s a fact that I can’t change. So the question becomes can I find some good in a rotten circumstance?

The following are the reasons I believe that I keep writing about suicide.

To Destigmatize the Topic: Is there any subject that remains as much of a taboo? Or more of a conversational record scratcher? I get it. It’s a rough, shocking, violent subject. I always feel like people are thinking “Can’t you write about something more fun? Like shingles, North Korea or the melting of the polar ice caps?” I could. But as long as the stigma remains potent, there is less likelihood people will seek help. That applies both to people experiencing suicide loss and people in mental anguish considering taking their own lives.

To Make People Feel Less Alone: This goes hand in hand with suicide’s taboo nature. People are afraid of talking about it because they don’t want to bum people out. Or because their family considers the cause of death embarrassing and worth shrouding in secrecy. But I have found that grieving silently can make you feel like a pariah. Like you and you are the only person to experience this set of feelings. It wasn’t until I wrote my first autobiographical piece about suicide did I realize how many people have lost somewhere dear to their own hands. Over two thousand people shared that article. Close to a thousand left me comments and I personally answered each one. So many of them said that sharing my experience made them feel less alone. The truth is, their honesty and compassion had the precise same effect on me.

To Process Old Wounds and the Ones That Still Persist: I’ve discovered, at least personally and anecdotally, that healing is an evolutionary process. I mean we’ve all seen This is Us. When you tragically and unexpectedly lose the family member you most admire, grief can continue to morph over a long period of time. For instance, the immediate shock and sadness may dissipate. And that can be replaced by a larger toll on the family. For example.

To Find Answers and/or Meaning: In my dad’s case, the initial shock and mystery began to clear up in the weeks after. Bills not paid, a mounting debt on the horizon. But as a writer and a human, I have desired answers not found on a spreadsheet. Like how much can we impute to the shame a man of a certain might feel when he’s no longer able to. Like what role a society’s obsession with wealth and things might play in impeding a man to admit perceived failure or weakness and ask for help. These are topics I’ve batted around in therapy. But there was something equally therapeutic about putting pen to paper. Which leads in to the next reason…

To Bring Myself Some Catharsis: The question I most often get from nice people after sharing my suicide story is “Was it cathartic to talk about?” Yes. A million times yes. That doesn’t mean it hasn’t been scary. That I haven’t felt incredibly vulnerable. That there hasn’t been immense blowback from some people who’d rather I kept our family secret a secret. But I can’t quantify how awesome it has personally felt to come clean. Like I mentioned it felt like I was carrying around an enormous psychic albatross. And now I feel lighter and more honest. Authentic and more transparent.

To Find My Own Voice. The truth is, I’ve found once I’ve talked about family suicide, opening up about aging, depression, career worries and overeating all seem easy. Now no topics feel off-limits — though my wife would prefer I don’t admit to having seen every episode of Blue Bloods. But truthfully, how could I become the kind of highly-personal memoirist I aspire to be if I haven’t included the the most emotionally resonant and salient piece of my personal puzzle.

To Possibly Save Others (But Really to Save Myself): The final reason I write about suicide is arguably the most difficult and personal to talk about. I know, I know, I’m already talking suicide. And yes, I do want to help people. I want them to know they can talk about mental hurt and there’s always someone out there to listen. I know with absolute moral certainty that I can’t bring my Dad back to this world. But what if talking about suicide and sharing our stories could save someone else’s Dad? I don’t presume to think I’m doing that. But it’s surely worth trying. And beyond that, I know my own propensity for melancholy and suicidal ideation. So I write about suicide to process my own emotions. I do it to hopefully never reach the lows my father did. And to remind myself what reaching those lows, left unchecked and unhealed, can do to the ones you love. So for all my high-minded and beneficent intent, I’m really not just writing to save other people’s lives. I’m writing also to save my own.